“How curious a land this is, – how full of untold story, of tragedy and laughter, and the rich legacy of human life; shadowed with a tragic past, and big with future promise!”

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folks

Histories and Legacies of Racial Violence in Georgia

Despite its founding on the idealist, egalitarian dreams of James Oglethorpe, Georgia quickly became a state defined by enslavement and plantation agriculture. In 1865, emancipation came slowly as formerly enslaved Black Georgians learned of their freedom from Union soldiers, other enslaved people, or even their enslavers who “spread the news by talking too freely” about the Confederacy’s surrender in their presence. During Reconstruction (1865-1871), Black Georgians gained significant rights in addition to their freedom. Unlike other ex-Confederate States, Georgia did not create “a harsh Black Code.” Freedpeople in Georgia gained property rights, legitimation of their marriages and children, and had access to the courts.1 They still faced significant economic hardships–as the federal government’s land program returned many of them to sharecropping on land owned by their former enslavers–or they faced discriminatory social practices and laws in seeking fair pay for their labor.2 They were also barred from voting, serving on a jury, or testifying against a White person in court.3

Jim Crow

In the last 1890s, Georgia passed numerous Jim Crow laws that mandated racial segregation rendering long-held social practices into law. Despite the principle of “separate but legal” established in Plessy v. Ferguson, life under Jim Crow meant widespread discrimination against African-Americans and other non-Whites. This discrimination was punctuated by episodes of racial violence–including massacres and lynchings–and terrorism perpetrated against African-Americans by White Georgians. In 1915, Wiliam J. Simmons recruited white American-born Protestant men to revive the Ku Klux Klan at Stone Mountain ten miles east of downtown Atlanta in DeKalb county. The Klan advocated militant white supremacy, anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism, and anti-immigration as well as “improved law enforcement, honest government, better public schools, and traditional family life.” Georgia’s KKK membership reached its height in 1925 at approximately 156,000 members.

In the face of this discrimination, Black Georgians built their own institutions, businesses, churches, schools, and neighborhoods. They also protested the Jim Crow laws through public demonstrations, petitioning the government, bringing court cases, and other forms of resistance.4 In Atlanta, Augusta, Rome, and Savannah, African-American residents boycotted local streetcars between 1900 and 1906 “to protest the enforcement of segregation ordinances that had previously gone unobserved.”

The Civil Rights Movement

After World War II, Jim Crow began to crumble, but it was not until passage of federal civil rights legislation in 1965 that legal segregation and discrimination came to an end. In 1946, Black Georgians achieved the right to vote after a federal court ruled in favor of Primus E. King, who had attempted to vote in the Democratic primary in Columbus, Georgia, in the King v. Chapman case. Within months of the final ruling, 116,000 Black Georgians had registered to vote.

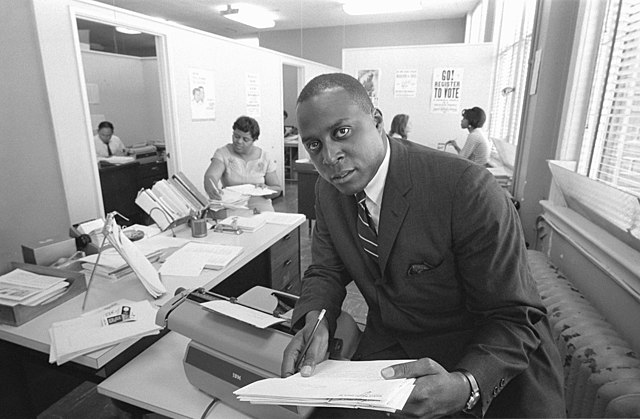

Georgia became a central hub of the Civil Rights Movement. As the headquarters of SNCC and the SCLC, Atlanta played a key role in the movement. Despite Mayor William B. Hartsfield’s successful campaign branding Atlanta as “The City Too Busy to Hate,” Atlanta students in Atlanta organized a “sophisticated and durable campaign” to end segregation in the city. Albany came to prominence in 1961 when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. became involved with a mass protest campaign, known as the Albany Movement, organized by local activists whose efforts were reinforced by three Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) workers—Charles Sherrod, Cordell Reagon, and Charles Jones. Civil rights activism in Albany continued after Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference moved on to Birmingham, Alabama. In Savannah, W. W. Law, head of the local NAACP, led a campaign over several years that forced city leaders to desegregate public and private facilities starting October 1, 1963.

The Ongoing Liberation Struggle

Although federal legislation brought a formal end to legal segregation and discrimination on the basis of race in 1965, Georgians continued to fight for the fulfillment of civil and human rights to African-Americans. New legal protections did not bring an end to police brutality, educational inequality, unemployment, poverty, inadequate housing, or policy brutality. In the 1970s, civil rights leaders sought to mobilize Black voters and to oppose “gerrymandering of political districts that decreased the power of the Black vote.”

In Georgia, we selected counties that reflect a range of historical experiences of racial violence, ranging from lynchings, terrorism, and physical violence to segregation, voter suppression, discrimination, and displacement during the Reconstruction Era 1865-1871, the Jim Crow Era 1876-1965, the Civil Rights Movement 1950-1968, and beyond. The counties reflect a mix of urban and rural sites, sites with documented episodes of intense racial violence or racial terror, documented sundown towns, and communities where the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Summer Community Organization and Political Education (SCOPE) Project mobilized and registered Black voters 1965-1966.

Documenting the historical landscapes of racial violence in Georgia through archival sources served as the foundation for this research. In interviews, the Georgia State University team focused on capturing the lived experiences of Black Georgians and on contemporary responses to racial violence and the ongoing legacies of segregation. In each county, the team focused on issues relevant to the local context and history.