Fulton County

Legacy, Memory, and Movement

Legacies of Racial Violence

Although Atlanta has earned a reputation as a Black Mecca in the minds of many Americans, the reality behind its nickname, “The City Too Busy to Hate,” reveals a city whose beliefs and practices have been deeply influenced by White supremacy. The Fulton County study connects the violence exacted by the Klu Klux Klan in the name of white supremacy to the ongoing challenges of police brutality. Through site visits, interviews and oral histories, we also highlight African Americans’ embodied memory of racial violence and the political geographies of resistance to oppression.

Political Geographies of Fulton county

Note: On some browsers you may need to zoom in or out to accurately display the map.

Connections of Violence:

Yesterday to Today

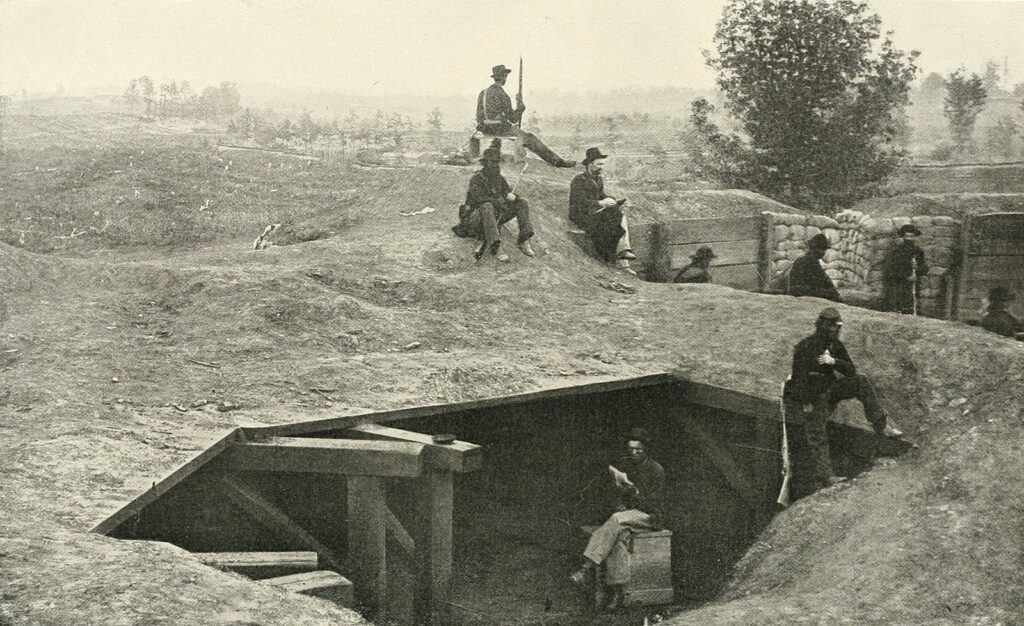

Reconstruction

In the years following the Civil War, racial violence was rampant. From county to county and state to state, there were rapes, lynchings, scalpings, drownings, and all manner of anti-black violence¹ at the hands of white individuals, mobs, and supremacist groups. Thanks to President Andrew Johnson’s pardons and amnesty, Reconstruction was overseen by the demoralized leaders of the Confederacy that lost the war.¹ Yes, it is true that after Emancipation “many Blacks walked off the plantation into the State House”, but by and large, Reconstruction failed to provide economic and democratic rights for Blacks.² President Lincoln never intended for blacks and whites to be equal socially or politically¹, the Supreme Court made several rulings that undermined the right to vote, citizenship, and the prohibition of segregation, and Black Codes ensured cheap labor and severely limited the rights of African Americans, yet Southern whites were still committed to persecuting and subjugating Blacks and exacting their hatred of the federal government onto the formerly enslaved.³ To do so, they “unleashed a reign of terror and anti-black violence.” ¹

The movement to reaffirm and preserve white supremacy became a concerted effort and as a result, supremacist groups were initiated across the South. Conditions became so vile, that after Johnson’s impeachment, President Grant urged Congress to pass legislation to thwart the savage violence taking place in the South. The result was the Klu Klux Klan Act of 1871. Although no one was convicted as a result of the Act it “enabled the federal government to use the full extent of its power to intervene in the prevailing lawlessness in the South and protect the rights of individuals. To ensure equal protection, federal law enforcement was empowered to intervene in southern states, and federal district attorneys could prosecute the Klan under federal law” (History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives.⁴

Once Democrats regained power, the KKK declined because there was no need for their enforcement. They rolled back any semblance of Reconstruction replacing it with Jim Crow Laws, yet many whites still felt the need to enact racialized violence.

The evolution of

State-sanctioned Violence

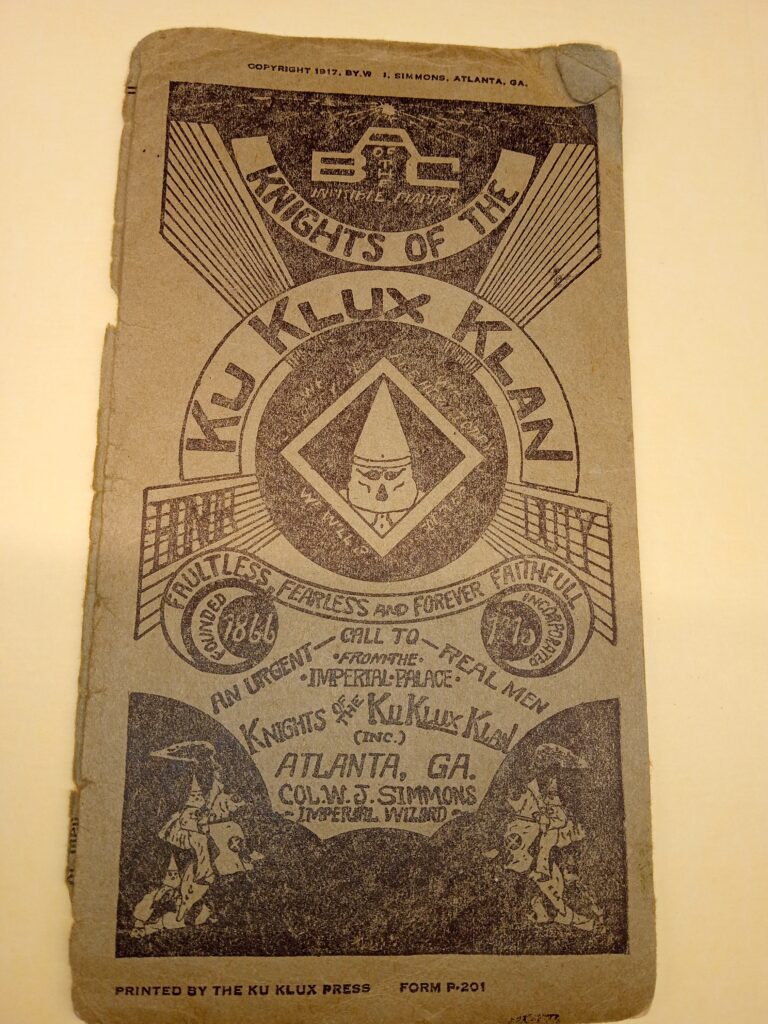

“In 1915, the film Birth of a Nation played for three weeks in Atlanta, portraying the Klan as a gallant organization saving the white South. The film broke all box office attendance records in the city. On Thanksgiving Day in 1916 white men gathered on the top of Stone Mountain to initiate the new secret order of the Atlanta Klu Klux Klan. Soon the organization spread north and west” The Klan grew rapidly, reaching an alleged membership of 4 million by 1925. Atlanta membership is hard to determine and estimates vary widely. East Point city attorney Harold Sheats admitted that the entire police department, mayor, and city council were members of the Klan so he joined too. They were also in the courts, and several Atlanta judges were klansmen.⁵

It should come as no surprise that law enforcement was fertile ground for KKK recruitment because policing as a Southern institution is an extension and incarnation of slave patrols. The inception and development of the American police can be traced to a multitude of historical, legal, and poli-economic conditions. “In 1704, the colony of Carolina developed the nation’s first slave patrol. Slave patrols helped to maintain the economic order and to assist the wealthy landowners in recovering and punishing slaves who essentially were considered property.” ⁶ Slave patrols were the first publicly funded police agencies in the American South. ⁷

Slave patrols remained in place during the Civil War. When slavery ended they merged with newly forming groups and became the federal military, state militia, and Ku Klux Klan to name a few. These new orders assumed the previous responsibilities of the slave patrols with increased virulence and violence. Whether by mutation, proximity, or linear progression these groups operated similarly to some of the newly established police departments in the United States.⁸ One such example is the Charleston Police Department. By 1837, there was 100 officers whose primary function was to regulate the movements of slaves and free blacks, checking documents, enforcing slave codes, guarding against slave revolts, and catching runaway slaves.” ⁹

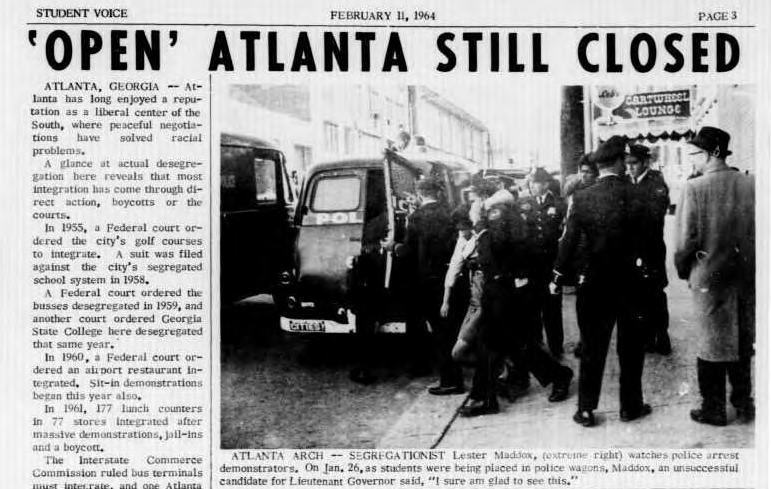

The Civil Rights Era

The 1960s were a bittersweet period in American history. The struggle for Civil Rights was at its apex and Atlanta, the birthplace of civil rights, played a pivotal role in fashioning leaders and undergirding the movement. Brave men and women across various walks of life from the North and South fought to begin to claim the country from the snares of racial hatred. Just as they had during Reconstruction, white southerners were committed to maintaining control, supremacy, and political and economic power by any means necessary. Among other advancements was the desegregation and inclusion of Blacks on police forces. Originally thought to be a good idea, it ultimately amounted to turmoil for Black communities. Residents testified that the Black cops were more vicious than their white counterparts (partially because they had to prove their allegiance to the force).

A pathway to Justice amidst the new paradigm of racial violence

Although Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, better known as the Klu Klux Klan Act, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1983, was enacted to combat persistent Southern lawlessness,” it went largely unfulfilled for almost 90 years because of narrow judicial interpretations of its provisions.” ¹⁰ In 1961, the Supreme Court in Monroe v. Pape interpreted “under color of” state law in a broad manner and as a result, section 1983 again became a potentially significant vehicle for redressing deprivations of civil rights. However, it was not until Monell v. Department of Social Services, in 1978 that municipalities were stripped of their absolute immunity from section 1983 liability.” ¹⁰ Today, the Monell claim is employed by Civil Rights attorneys whose clients have had their constitutional rights violated by police officers, black and white. The Monell Claim asserts that the official acted unconstitutionally due to a pattern, practice, or policy within the municipality or the police force (S. Williams, personal communication, November 8, 2023). Even in the 21st Century, the practices that developed from the slave patrollers and those trying to maintain the hierarchy of race and class are still pervasive.

Forced Displacement

While racial violence involves direct acts intended to harm, injure, damage, kill, or instill fear based on an individual’s perceived race, racialized violence encompasses symbolic, structural, or systemic forms of violence that relate to race. One significant yet often overlooked form of racialized violence that Black residents of Atlanta have perpetually faced is forced displacement. This type of displacement, driven by state-sanctioned actions, refers to the involuntary or coerced movement of individuals or entire communities from their geographic locations or spatial status. Such injustices have been used to uphold white supremacy and promote a race-based capitalist system, and sometimes even to placate the Black bourgeoisie. This is executed through various means, including segregation, neighborhood clearance, enforcement of tenant and Black codes, direct violence, excessive policing, intimidation, urban renewal, and gentrification. The consequences of forced displacement are extensive, leading to a decline in social cohesion, fragmentation of families, increased health issues,¹ disparate exposure to neighborhood poverty and socioeconomic challenges, trauma, instability, loss of social networks, financial strain, and overcrowding.

Serial displacement in Atlanta

In 1933, Tech Flats, a mixed slum neighborhood, was demolished to “enhance the value of the central business properties”.² This statement comes from Charles Palmer, a real estate developer who represented the city, working alongside the newly established Public Works Administration, which was part of President Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. Under the same program, John Hope, the African American president of the historic Atlanta University, advocated for the clearing of Beaver Slide, an adjacent African American community. Due to segregation, the majority of Blacks who lost their homes in Tech Flats were not allowed to move into the new, all-White Techwood public housing units that replaced their neighborhood. Furthermore, most former residents of Beaver Slide were deemed ineligible for the new University Homes public housing, as the rent and eligibility requirements effectively catered only to Black middle-class families.

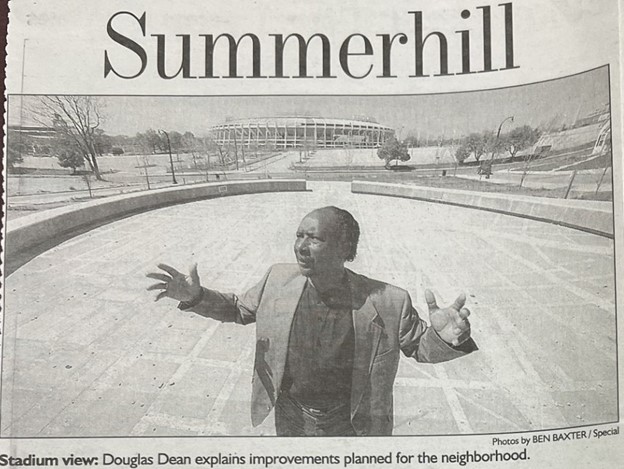

The Federal Housing Act of 1949 granted local governments the authority to use eminent domain to seize land from one group of owners and transfer it to another, allowing for a change in its intended use while compensating the previous owners with federal funds.³ During the 1960s, this practice led to the destruction of three Black communities: (1) the Butler Street residences, which were replaced by a hotel; (2) Buttermilk Bottoms, which became the Atlanta Civic Center; and (3) the Rawson-Washington projects, which were demolished to make way for the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, even though there was no team designated to play there at that time. The Community Council of the Atlanta Area published a report detailing how the redevelopment of Rawson-Washington (located in the Summerhill community) forced 10,000 Black residents to live on just 354 acres.⁴ The impact on those whose families, home lives, and welfare were deeply intertwined with the community’s residences, practices, public spaces, churches, and small businesses was devastating.

During the same period in Atlanta and in major metropolitan areas across the nation, overt and pervasive racism manifested through highway construction, which was purposefully aimed at the destruction of African American neighborhoods.⁵ Highways were employed not only as a pretext for demolishing black communities but also acted as de facto boundaries separating white and black neighborhoods once constructed. A city planning report from Atlanta in 1960 explicitly stated that the layout of Interstate 20 to the west of downtown would create a delineation between the white and African American communities.

I told you about my friends, we threw [news]paper. We walked across that expressway when they were building it. I came from Summerhill, and I walked across the freeway to get to Pulliam Street on the other side.

-Douglas Dean⁶

Former State Representative Douglas Dean, a 78-year-old lifelong member of the community, personally recalled the loss. His grandmother first moved into the Summerhill neighborhood in 1905, and three generations later, he raised his children there as well. “Here’s something I bet you didn’t know. Piedmont Hospital was on Crumley and Capitol Ave. before they moved it to Piedmont Avenue and tore it down for the stadium and parking”. Mr. Dean went on proudly boasting that “before the expressway, we had 7 supermarkets”.⁶ The soon-to-be octogenarian listed Austin Supermarket, Colonial Supermarket, Beulah Supermarket, Westner Supermarket, and Barnett Supermarket without hesitation. He cited French’s Ice Cream, Jacob’s Drug, and the library that was located at the corner of Capitol and Georgia Avenues among the businesses that were eventually lost due to the development of the expressway and the stadium.

In preparation for the 1996 Olympic Games, influential stakeholders within the city expressed concern that accommodating Olympic athletes in neighborhoods characterized by high crime rates would reflect poorly on Atlanta. This perspective aligned with the objectives of Mayor Bill Campbell’s administration and the housing strategy under the leadership of Atlanta Housing Authority (AHA) appointee, Renee Glover. Due to white flight and the segregation of Black residents to specific areas of the city, Techwood Homes—originally the first site designated for clearance in the 1930s—evolved into a predominantly Black housing project. This community, along with Clark Howell Homes, faced another cycle of clearance. Consequently, by 1996, while over 1,300 new and rehabilitated housing units emerged in the targeted neighborhoods, the demolition of 3,400 housing units resulted in a net loss of at least 2,100 units.⁷ The AHA executed this plan in a manner that effectively involved forced removal, circumventing the necessity to rehouse or construct an adequate number of units to accommodate the displaced residents. This approach was implemented despite federal mandates and commitments made to the original residents. The Olympic redevelopment, often referred to as the formation of mixed-income communities, served as a façade to facilitate the displacement of economically disadvantaged Black residents from the downtown area⁸.

Atlanta Apartheid

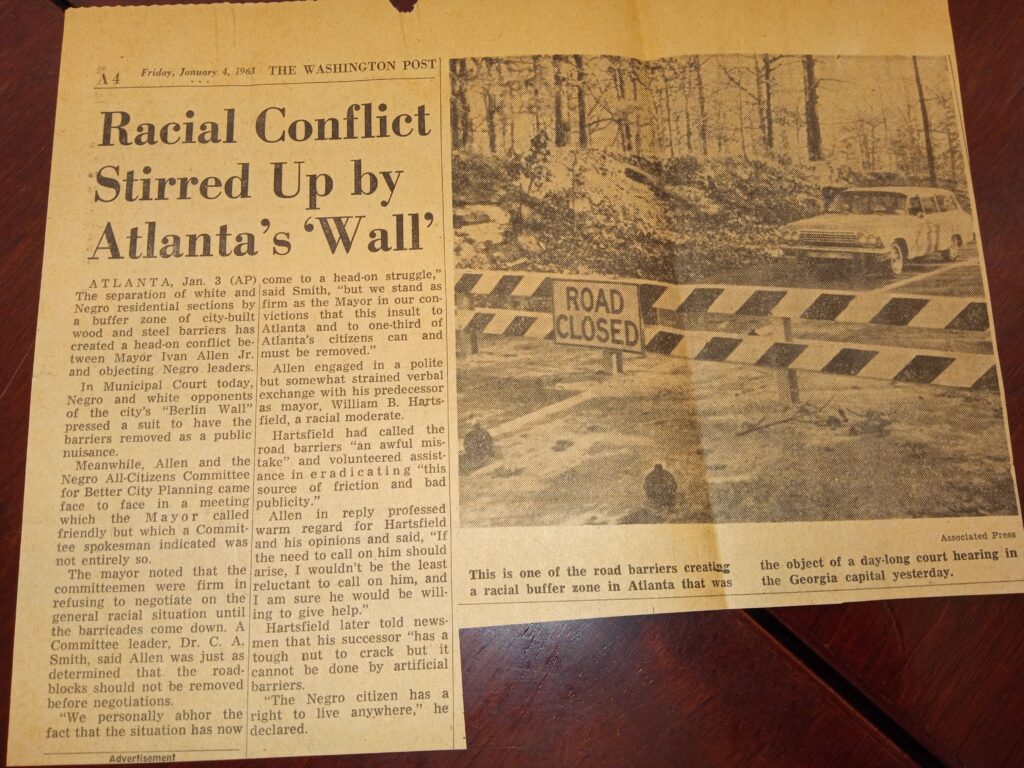

South Africa’s institutionalized system of White Supremacy, subjugation, and racial segregation was known as Apartheid. Perhaps one of the most familiar images that people around the world associate with South African apartheid is the roadblocks. In Atlanta, various racial buffers were used to keep African Americans in their place and maintain housing segregation. Among these were street name changes, such as Courtland Street and Juniper Street, and Monroe Drive and Boulevard, to ensure that Blacks and whites didn’t share the same street address. But, there were also city ordinances and physical blockades.

In December of 1962, a subcommittee of the city’s Board of Aldermen approved Mayor Ivan Allen’s proposal for a buffer zone in southwest Atlanta in response to white complaints that African Americans were moving into the Peyton-Utoy Forest neighborhood. Dr. Clinton Warner, an African American surgeon, had recently purchased a house in the white community⁹. There were also rumors of “block-busting”¹⁰, a housing desegregation tactic used to resist the idea that African Americans could not live in certain areas and thwart the system that sought to keep them out by infiltrating and desegregating white neighborhoods. Black real estate brokers and agitators would call white homeowners requesting to purchase their homes and conspicuously drive through the neighborhood. White homeowners would panic, and some even sold their homes, creating a vacancy amid fear and low demand, which allowed African Americans to purchase the homes in the segregated community. Immediately after the approval, the concrete and wood structures were placed on Peyton Road and Harland Road on December 18th¹¹. Once again, city leaders went on record and stated that the barriers were meant to stabilize boundaries between whites and Negroes in the Peyton community. Likened to the Berlin Wall, what came to be known as the Atlanta Wall was not only a symbol to remind Blacks of their place in the city, but it was a physical tool used by officials to keep them out of white spaces.

Although the wall was the brainchild of white homeowners in the neighborhood¹⁰, and Mayor Allen had the support of city officials and a judge who initially upheld the wall as legal, the response and opposition to the wall was quick, multi-racial, intense¹², intergenerational, and came from as far as New York¹³. Three white residents who lived in the community of focus partnered with two Black residents who lived in an adjacent community to hire Civil Rights attorney Donald Lee Hollowell to file a lawsuit to remove the barrier. College students led protests at white businesses, there were demonstrations at the sites of the blockades, and people wrote to Mayor Allen to voice their disapproval, disappointment, and to encourage him to remove the Atlanta Wall. Less than four months after the wall was established, a superior court judge determined that the wall was unconstitutional, and it was removed in early March.

Works Cited:

- Anderson, C. (2017). White rage: the unspoken truth of our racial divide (Paperback edition). New York: Bloomsbury, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Wilson, W. J. (2012). The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy (Second edition.). Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1995). Black Reconstruction in America (1st Touchstone ed.). Simon & Schuster.

- 4. History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “In Pursuit of “Practical Freedom,” https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Fifteenth-Amendment/Civil-Rights-Act-of-1875/ (January 14, 2024)

- The Ku Klux Klan in Atlanta, Cassette: 31. Living Atlanta oral history collection, aarllivingatlanta. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History.

- Kappeler, V. (2014, January 7). A Brief History of Slavery and the Origins of American Policing. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from EKU Online website: https://ekuonline.eku.edu/blog/police-studies/brief-history-slavery-and-origins-american-policing/

- Walker, S. (1998). Popular justice: a history of American criminal justice (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Durr, M. (2015). What is the Difference between Slave Patrols and Modern Day Policing? Institutional Violence in a Community of Color. Critical Sociology, 41(6), 873-879. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920515594766

- Barlow DE and Barlow MH (1999) A political economy of community policing. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 22: 646–674

- Thomas, D. (1978). Governmental Liability Under Section 1983 and the Fourteenth Amendment After Monell. St. John’s Law Review Volume 53, Fall.