Forsyth County

Displacement, Marches, and Mythology

A history of Repeated Displacement

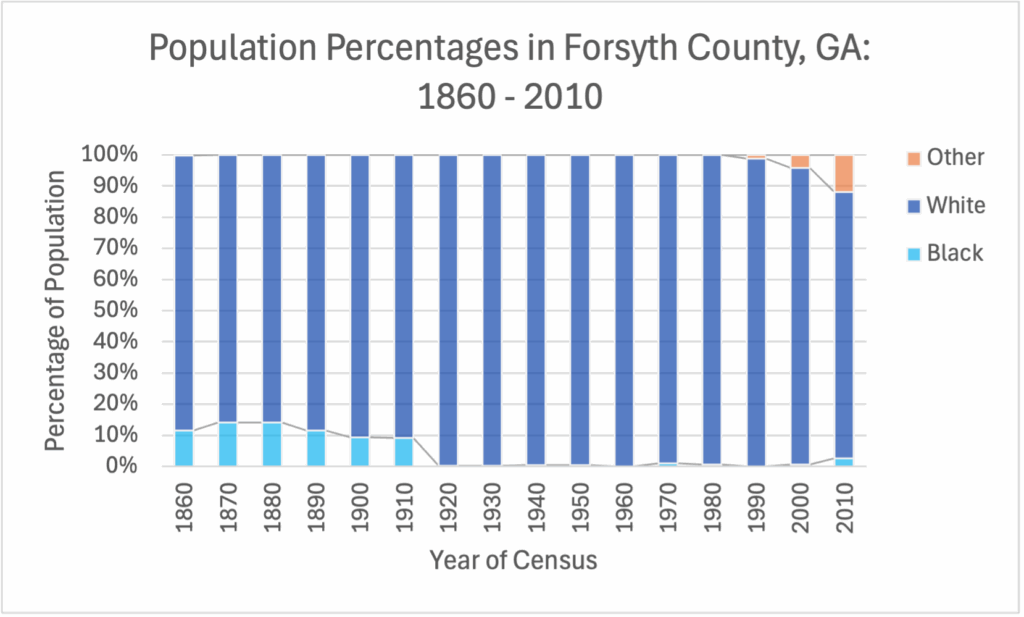

Today, Forsyth County is known for its top-ranked public schools, high quality of life, strong economy, safety, affordability, and natural beauty. However, its history of racial violence, reputation as as a ‘sundown town,’ and lack of diversity continue to influence how Georgians navigate Forsyth. The 1912 expulsion of Black residents of Forsyth County is a defining event in Georgia’s history. Since the 1912 tragedy, Forsyth County has experienced long periods of relative peace interspersed with moments of social conflict. The general economic prosperity of Forsyth, combined with rapid economic growth over the past 20 years, has increased the county’s diversity. Yet Forsyth’s turbulent past continues to haunt Black Georgians who are reluctant to live, work, or visit the county. Recent efforts to reckon with this difficult history and create a better future offer hope of lasting change.

1912 lynchings and expulsions

In Forsyth County, 1912 was a period of intense racial violence. A local man, Tony Howell, was accused by Ellen Grice of breaking into her home and appearing in her bed, whipping up white Forsyth residents into a frenzy. Then, multiple men were killed for the assault of Mae Crow, a white woman. While her assault is undoubtedly a tragedy, she never woke up from her injuries to accuse anyone before she perished. Mobs formed around the Cumming Courthouse, and Rob Edwards, one of the accused, was lynched. State troopers were called in to keep further violence from erupting. They escorted Oscar Daniels and Ernest Knox, the other accused, to Fulton County Jail to keep them safe until their trial. Then, after a speedy trial, the two young men were hung publicly, despite promises that it would be a private execution. During the trial and afterward, night riders rode around on horses and threatened the small, remaining Black population of Forsyth to leave or else. Some had their homes and belongings burnt down if they did not comply. Soon, there were no Black people remaining in the county.

The story of 1912 is tragic and more complex than the overview given here. For a more in-depth look at the expulsion, we recommend listening to the 1912 Podcast by the Atlanta History Center or reading other Atlanta History Center material on 1912. Our narrative will focus on two more recent stories in Forsyth’s history that showcase displacement, violence, community organizing, and the ongoing effort to heal. Below the narrative is a timeline that explores important events in Forsyth County’s history in a different way.

The marches

By 1987, Lake Lanier had helped transform Forsyth County from a rural, isolated farming town into a thriving tourist destination and quiet place for Atlantans to move. With an influx of tourists coming into the county to enjoy recreational activities there, some liked it enough to move there permanently. Outsiders with different perspectives on issues like segregation and racism moved in and butted heads with long-time residents. Not all residents whose families were involved in the 1912 expulsion were proud of it, and not all residents wanted Forsyth to stay an all-white county. Still, some loud, persistent residents of Forsyth wanted everything to stay the same, and those kinds of ideas caused a flare-up of violence when Chuck Blackburn tried to organize a Martin Luther King Day march in 1987.

Chuck Blackburn ran a karate school in Forsyth. He saw MLK Day as an opportunity to strengthen the fraught relationship between Black and white people in Forsyth. So, he organized a Brotherhood March for that day and advertised it in the local newspaper. Unfortunately, this led to his karate school getting bombarded with phone calls threatening Mr. Blackburn and his business, telling him to stop what he was doing or else. This understandably frightened him, and he called off the march. Then Dean Carter, a friend of Mr. Blackburn’s, picked up the effort and got civil rights leader Hosea Williams involved. Together, they gathered 75 people to march with them on January 17th, 1987.

The plan was to march to the Cumming Courthouse, where Rob Edwards had been lynched in 1912. The sheer number of white supremacist counter-protestors made that impossible. A portion of them were KKK members wearing their white robes, but many of the counter-protestors were simply people from the area that did not welcome Carter and Williams’s message. They greatly outnumbered the Brotherhood marchers, and some of them instigated violence. People threw bottles and rocks at the marchers, and the mob of counter-protestors got so unruly that police stepped in to escort the Brotherhood marchers out of harm’s way.

While Forsyth’s reputation as a town with a history of racial violence was known by local residents, the violence and hatred towards the Brotherhood marchers made national headlines, putting a spotlight on the county and its history. On January 24th, 1987, an estimate of 20,000 people showed up to march along Highway 9 to the Cumming Courthouse for another civil rights march. This decisive action by civil rights leaders and activists set in motion the largest civil rights march since the 1960’s. Thousands of like-minded people deciding to demand change is still cause for hope, decades later. National media coverage and the new Oprah Winfrey show sparked conversation on a national level.

Afterwards, smaller marches set up by white supremacists continued in Forsyth. In March of 1987, and on January 26th, 1988, white supremacists marched to the Cumming Courthouse in a distorted mirror-image of previous marches for justice. Thankfully, no more violence was committed, and they did not stir up the same hateful chaos as in January of 1987, but their ability to march at all shows that the work is not over yet.

In response to the marches and the publicity generated by them, two committees were formed by Governor Harris to investigate land theft and loss in Forsyth County. One committee was made up of white Forsyth residents and the other was made up of Black Atlanta residents. The Black committee had a goal of getting reparations for the stolen land, in the form of money or land. They felt that reparations could help heal some of the trauma of the 1912 expulsions. The white committee presented a report stating that no land was stolen, while the Black committee presented an incomplete report. Their interview evidence showed that land had been stolen from Black people in Forsyth County, but they did not get a chance to examine tax records. This made their report seem less based on fact than the white committee’s report. Governor Harris decided that because the reports did not agree, no actions would be taken to make reparations or investigate further. While extremely disappointing, Harris’s dismissal was a continuation of the pattern of willful ignorance set by government officials.

There have not been any major marches in Forsyth County since the ’80’s, but they still mark an important chapter in Forsyth’s history. They brought Forsyth to the forefront of national awareness and caused attempts to reckon with the past and change the future.

Lake lanier

The waters of Lake Lanier hide a painful history. Many people believe the lake was built to drown the Black town of Oscarville, but the true story tells us even more about how people deal with racism and loss. Lake Lanier was dammed in the 1950’s using federal government funds. It was originally intended for hydroelectric power, flood control, and a water source, but over time it became a recreational area as well. Thousands of acres of land were used to create the lake, and the government bought them using eminent domain. Landowners and residents were given six years to move in preparation to build Buford Dam. Oscarville is one of the towns that ended up flooded by Lake Lanier, but the displacement of Black people in Oscarville took place long before 1950.

Oscarville was a small, multi-race community in Forsyth County, with a Black population of approximately 10% in 1912. It wasn’t destroyed to make the lake or to cover up past racial violence, but it was violently emptied in 1912 when night riders forced out nearly all Black residents. Families were threatened, homes were burned, and many were killed or jailed, all in the name of justice for Mae Crow. By the time the government built the Buford Dam in the 1950s, Black people were already gone. Their land was taken or sold under pressure after the 1912 expulsions, and the lake covered what was left.

Over time, stories of ghosts and drowned towns grew. They became a way for people to make sense of a painful history that was never fully faced. Oscarville became a symbol, part of a larger myth about Black towns lost to water, even though the truth is more painful. These sensationalist stories can help people make sense of the past, but they can also hide the real facts: that Oscarville was erased by racist violence, not just water. Even so, Oscarville’s memory survives in family stories, community work, and efforts to protect cemeteries that tell the truth. Oscarville wasn’t drowned, but it was buried in silence. If we look closely, the lake reflects not just a pretty view, but a history that still needs healing. The real haunting isn’t from ghosts; it’s from the people who were pushed out, and the truth we’re still learning to face.

Forsyth in the present day

In recent years especially, Forsyth has come together as a community to reckon with the past and try to create a better future. There has been little acknowledgement by government officials of wrongs committed against the Black people of Forsyth. Despite that, county residents, descendants of people forced out of the county, and others have taken on the challenge of what to do next. In 2021, a local organization, the Forsyth County Remembrance Project, partnered with the national organization Equal Justice Initiative to memorialize Rob Edwards outside the Cumming Courthouse, bringing awareness and some measure of healing. Local churches have organized a scholarship for descendants of those expelled from Forsyth to be able to attend college. The Atlanta History Center partnered with WABE to create the 1912 podcast and exhibits in 2024. Together, a better future is being created.

Timeline of violence and resistance

Below is a timeline of the impact of racial violence in Forsyth County, Georgia beginning with the expulsion of black residents in 1912. The timeline traces the incidences of violence, their outcomes, and responses during the 1912-2021 period. This timeline also includes community efforts of descendants and residents of Forsyth County to continue pushing for change and healing.