Clarke County

African American Communities, Displacement, and Responses to Legacies of Violence

Map of Athens by William Winstead Thomas,1874, reprinted by the Athens Historical Society in 1974

Introduction

Slavery and the emotions and marks it created in our memories have impacted all aspects of American life. It is important to remember that African American people have a strong history of anti-violence efforts and creative responses to racial violence, especially in the United States South. We discuss the history of racial violence that includes lynchings and forced removal of African Americans from their communities as well as African American responses to the violence. This section discusses events in what is now Clarke County, Georgia, home to the City of Athens and the University of Georgia. It includes some important events in nearby Oconee County.

The Role of the University of Georgia

The history of Clarke County is intertwined with the history of the University of Georgia, founded in 1785. Many early Southern institutions were built upon the foundation of slavery and forced free human labor. The University of Georgia (UGA), located in Athens, symbolizes this history with deep-rooted connections to slavery that have influenced the university’s culture, economy, and social fabric. We address the university’s role in the forced displacement of Reese Street and Linnentown residents due to federal “urban renewal” programs.

Athens Confederate Monument-A Place of Power, Politics and Protest

On May 5th, 1871, during the Reconstruction Era, the Athens Confederate Monument was built by the forced labor of enslaved Black people. It symbolized the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the systematic dismantling of Black political leadership and voting rights. Specifically, it was built to honor the memory of 217 local Confederate soldiers who died in the Civil War and includes inscriptions of language directly linked to the KKK.

The Athens Confederate Monument promoted the “Lost Cause” (“brave and honorable White southern men fought and died for a ‘lost cause”)-emphasizing the bravery of Confederate soldiers rather than discussing civil rights, racial legacies, and the brutality of enslaved Africans.

The monument occupied a prominent and visible spot across from the famous UGA arch. The monument quickly became a symbol associated with both Southern pride and culture and Black terror. Black students, community organizers, and allies have called on UGA to address the message this monument sends to its marginalized, specifically Black students on campus.

Despite the racist history of this monument, efforts to relocate it faced a lot of resistance. In 2019, in an attempt to stop the national momentum to remove Confederate monuments, Georgia’s Senate Bill 77 was signed into law by Governor Kemp, making it illegal to move these monuments unless they required construction, repair, or relocation. The law lists strong penalties for anyone who attempts to remove them.

The Official Code of Georgia states that individuals will face more severe penalties for tampering with Confederate monuments than they would for committing a hate crime. This state code protects racist symbols associated with a divisive and oppressive past instead of addressing acts of prejudice and violence targeting Black and marginalized communities.

The university was notably silent about the law and did not address the historical implications of this enduring symbol. The legacy of problematic historical figures extends to several UGA buildings named for individuals associated with racial violence. These buildings and halls include Henry D Gravy, Russel Special Collections, Moore College, Candler Hall, Park Hall, Lumpkin House, Mell Hall, Rutherford Hall, Wray-Nicholson Hall, Lumpkin House, and Milledge Hall.

In June 2020, in the wake of the national wave of protests that followed the May 25 death of George Floyd, the Athens-Clarke County Commission voted to remove the monument from Broad Street. The monument has been moved to Timothy Place off Macon Highway.

Below Baldwin

On November 17, 2015, construction workers discovered human remains beneath Baldwin Hall on UGA’s campus. As construction workers unearthed the remains, it became clear through DNA testing that these individuals were once enslaved African people. This tragic history reinforced a painful but necessary acknowledgment of the university’s past ties to slavery.

The rapid relocation of the burial remains to Oconee Hill Cemetery, a formerly segregated burial ground, without speaking with the local Black community, evoked deep pain and anger. Community members demanded that the remains be laid to rest in sacred grounds made for African Americans, such as the Brooklyn Cemetery and Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery.

These historically Black cemeteries in Athens have remained largely neglected due to structures of racism, including a lack of funding. By moving the remains without input from descendant communities, UGA denied families the opportunity to reconnect with their ancestral memories and past. Further, the community was unable to attend the reburial ceremony, and their voices were not heard in the planning for a resolution and the removal of the remains below Baldwin. The lack of engagement with the community continued historical patterns of disrespect and attempted silencing of Black voices and experiences.

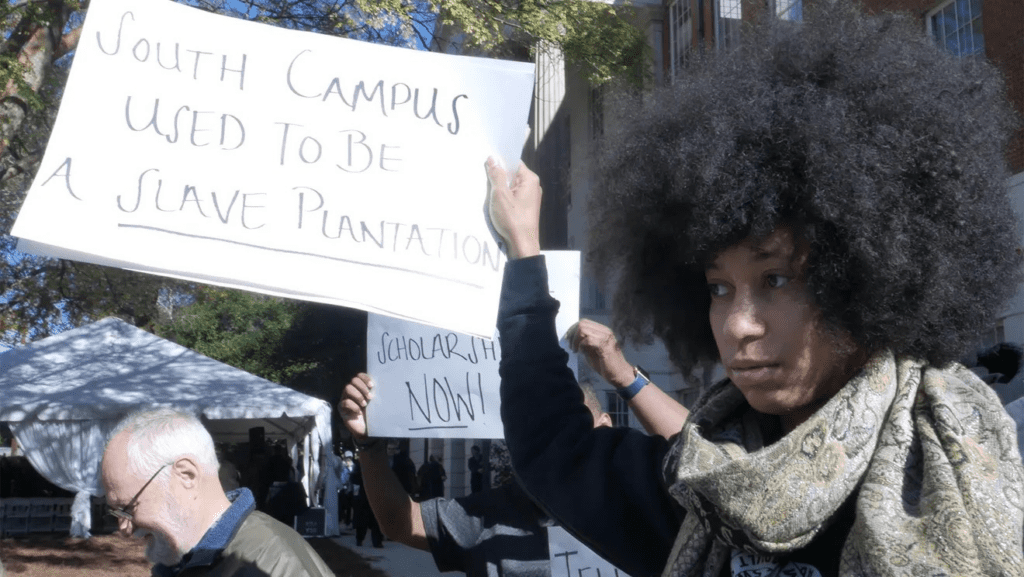

During the Memorial Commemoration on November 16, 2018, Athens organizers, students, and local community members demanded redress for the legacy of slavery at UGA. However, UGA’s response to community concerns was disappointing. President Moore’s dismissal of social justice organizations’ efforts further fueled the outcry from the community. Proposed solutions, such as establishing scholarships, raising the pay of all full/part-time employees to at least $15 an hour, and funding a university center on slavery, were refused. Tensions increased between the university and the community.

The community called for concrete actions to address systemic injustices. On April 29, 2019–four years after discovering the remains, another series of peaceful demonstrations took place. UGA’s response remained dismissive, and UGA police denied the protestors’ request for a meeting with President Moore.

Students, along with university and Athens community members, continue to draw attention to the need for healing and reconciliation. UGA and other institutions with racist pasts should heed these calls for action and engage in genuine dialogue with affected communities to create lasting change.

Reese Street Historic District: An Educational Center for Black Communities

AHIS moved to Dearing Street in 1958, and the original building was sold to the Athens Masonic Association, Inc. in 1960.

Forced displacement of linnentown

Linnentown was an African-American community of over 55 families next to the University of Georgia (UGA) in Athens, Georgia. Life in Linnentown was characterized by a strong sense of community and acted as a space where African Americans could resist the daily abuse of racism. The community thrived despite the challenges of segregation and limited resources. In the 1960s, Linnentown faced a devastating blow. UGA and the city of Athens undertook an urban renewal project, which means Negro removal, according to the American civil rights activist and writer James Baldwin, in order to build UGA high-rise dorms Creswell, Brumby, and Russell Hall. They labeled Linnentown as a “total slum” in order to justify this forced and violent displacement. However, many Linnentown residents were from middle-class families who owned their homes and were skilled workers, gardeners, handymen, and cooks. After the forced removal of Linnentown residents, many families sought public housing and were pushed into generational poverty. According to Ms. Whitehead, a descendant of Linnentown, many families never recovered from this.

Decades after the destruction of Linnentown, former residents and their descendants began advocating for recognition and justice. Community-led initiatives, such as the Linnentown Project, have drafted historic legislation that provides recognition and redress for the harms caused by Athens’ urban renewal. It is the first legislation of its kind that calls for reparations for Jim Crow-era discriminatory practices by federal, state, and local public institutions.

On June 23, 2024, the Athens Reparations Action gave 19 families of Linnentown their first checks. They raised $120,000, mostly from private donations. These efforts to preserve the memory of Linnentown and reconcile with the racist history of the past have resulted in such impactful breakthroughs. Although more work has to be done, this financial support is a step towards acknowledging the injustices faced by Linnentown residents and aiding their descendants.

Resources to learn more about Linnentown: