Chatham County

Remembrance Work: Truth and Unity

A culture of remembrance

At the heart of Southern Wake Work are innovative responses to racial violence and its legacies: acts of storytelling, artistic expression, and community organizing that resist erasure, challenge dominant narratives, and foster collective healing. In this section, we refer to these activities as “remembrance work”. The individuals, organizations, and communities in Savannah, Chatham County, and throughout the coastal Georgia region faced the past head-on and adopted remembrance and re-telling as a strategy for remaking their communities in the aftermath of racial violence.

WAQUL JAA AL HAQQU, the truth has arrived

His voice is loud enough for everyone to hear. WAQUL JAA AL HAQQU, WAQUL JAA AL HAQQU. Without strain or overmodulation, the rise and fall of his intonation drew us in, made us reflect, challenged our schemas, scolded our lack of consideration, and then gave us hope and a clarion call. His power resided in his spoken word. He possessed the ability to recall history- stories that were once lost in time, forgotten in the shadows, misrepresented, or seldom acknowledged. African history, Savannah history, Gullah-Geechee history, Black history, Georgia history, American history. Notice his potency in the passage below as he brought the echoes of the past into that present moment:

St. Cyprian represents all of that right now. It represents life, it represents reclamation, resurrection, change. It represents foundation that is necessary right now when we celebrate and talk about this day. But sometimes it gets lost because we like to do something else. There’s a movie called Romancing the Stone. And that’s what we do, we romance the stone. We romance the story… An event took place at the Georgia Historical Society over a decade ago. I’m sitting inside the place and I’m listening to this person talk about history that’s tied to Macintosh County, Georgia. I listened to a person talking, and that person had an almost romantic view of the story that was being conveyed to the people. When it was time for the question and answer, I raised my hand. I had to say something. I said rice plantations were some of the most horrible plantations you could ever imagine. People talk about the sugar cane plantations, but the rice plantations were worse. And then the person said, “Yes, you’re right. Yes, they were awful”. And then I talked about somebody by the name of Roswell King. I said Roswell King was no hero- a straight villain- he did not respect African people. The person said, “Well, I did a presentation in Darien, and there were these Black women who came there, and they were proud to be descendants of Roswell King”. So I’m sitting there mortified now. Mortified because I’m saying you cannot legitimize insanity to me.¹

St. Cyprian Episcopal Church Commemoration, Weeping Time Commemoration 25′

Amir-Jamal Toure`, the oral guide, the admonisher, the consoler, the professor, is an amalgamation of many identities. Gullah/Geechee, Djeli, a Muslim, and a Black man born and raised in Hilton Head and Savannah- the American South. His role is greater than that of a simple historian- he is a social commentator, a culture bearer, and one who both preserves and embodies the history of the people in the Coastal Georgia region. This role has become his identity and lifelong mission. He continually pays homage to his ancestors, believing that their strength and journey have had a profoundly positive impact on his own life. He maintains a posture of reverence for them, understanding that their struggles and resilience deserve to be honored and respected. He is committed to ensuring the past is never forgotten.

Note: Click the three dotted lines then picture in picture to see full screen

Remembrance Work

The vignette above is a summary of our team’s encounters with Jamal Toure` over a three-year period. It embodies the essence of remembrance throughout Savannah-Chatham County. According to the remembrance workers we observed, interviewed, and had as guides, the coastal Georgia region is rife with a history of racial violence, yet the tragic tales abound with triumph because many resisted, overcame, built, and amassed dignity despite the brutal conditions. What we discovered during our fieldwork is that stories had variations and were told in different ways, even among the Black remembrance workers. In some instances, this was due to conflicting source material; in other scenarios, people unintentionally misspoke; but sometimes history was reimagined as a subconscious strategy of remaking. In Professor Toure`’s vignette, he spoke of a second-hand account of Blacks who minimized the atrocities and clung to certain aspects of history without considering the full weight of the actions of the perpetrator and suffering of the victims. Truth was a concept and priority that was consistently encountered in the coastal region, but similar to the accounts of the Gospels of Jesus Christ, the Bhagavad Gita, or Moses and the Ten Commandments, the facticity of a story and its ability to convey truths may or may not be one and the same.

The remembrance workers we encountered were consistent in their commitment and vision to reveal the truth and to use that truth as a method to honor the ancestors who endured cruelty and to harness the stories of their strength as a source of pride and empowerment in the present. The Savannah-Chatham County remembrance workers that we have encountered from the Beach Institute African-American Cultural Center, Ralph Gilbert Museum, First African Baptist Church, Tybee MLK, Weeping Time Commemoration Committee, Organiztion to Commemorate African American enslaved people Nationally, Day Clean Journeys, Discover Black Savannah, and the Harambee House utilize storytelling, community organizing, commemoration, research, tours, collection and preservation, and the celebration of Blackness to forge pathways of hope, resilience, truth, justice, reconciliation, and tenacity from the past to the present and into the future.

Political Geographies of Chathem county

Note: On some browsers you may need to zoom in or out to accurately display the map.

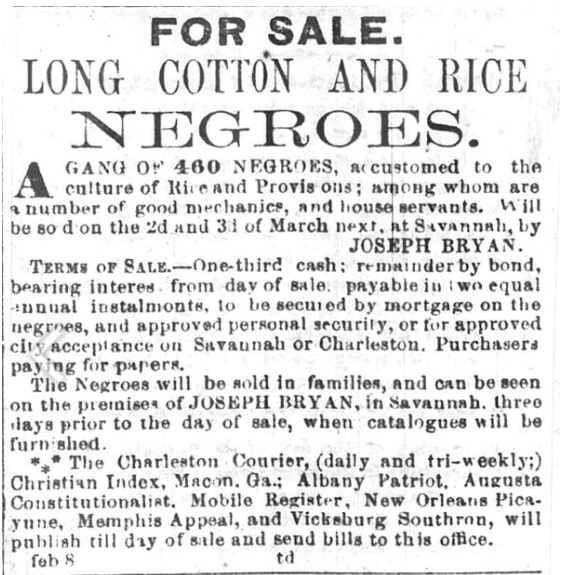

Weeping Time

The Weeping Time refers to an enslaved people’s auction that is considered one of, if not the largest, “documented” sales of enslaved persons in the United States.² This tragic event is remembered every year in Savannah and throughout Chatham and McIntosh counties with a series of events that are held the first weekend in March. Historical records, including newspaper articles, auction advertisements, and personal accounts, confirm that the sale occurred over two days, specifically March 2nd and 3rd in 1859. Mortimer Thomson, writing under the pseudonym Philander Doesticks for the New York Tribune, produced what many researchers regard as a scathing exposé of the auction.² His account delved into the social climate in Savannah days before the sale and detailed the circumstances under which Pierce Butler was forced to auction off his property and the people he had enslaved. He recounted the families that were torn apart, shared brief narratives of the negotiations, and listed the astonishing prices at which they were sold. Thomson poignantly noted, “As the last family stepped down from the block, the rain ceased; for the first time in four days, the clouds broke away, and the soft sunlight fell on the scene.” ³ The sentiment that is commonly shared during the retelling of the events is that it was as if the heavens were weeping for the horrors that took place, which is how the term “Weeping Time” came to be.²

Weeping Time is not a commemoration of enslaved people’s auction; rather, it is a time to remember and honor the people who were traded as if they were simple commodities. The enslaved individuals were taken to Savannah from the two Pierce Butler plantations: one on St. Simon’s Island in Georgia and the other on Butler Island near Darien, Georgia. Savannah was close in distance and a bustling center for commerce. The auction was held at a horse racing track, on the same land that now houses Otis J. Brock III Elementary School.² Auction records show that 436 were on the auction bill, and 429 enslaved people were sold.³ Historians, researchers, genealogists, and Weeping Time enthusiasts dedicate a significant amount of time year-round excavating the history, lives, and lineages of those who were sold, the plantation as a geographical site, the enslaved peoples’ owners, and the descendants of those who were sold. During the 2025 Weeping Time Commemoration, Dr. Kwesi DeGraft-Hanson, one of the premier researchers of the Weeping Time auction, detailed how his research led him to discover a fourth-generation descendant of John Butler, who was one of the 429 that were sold. Despite being born in California and living there her entire life, the remembrance of Weeping Time forged a connection between the descendant, all those who endeavor to honor the victims, and John Butler’s name and story, ensuring that it did not end on the auction block in 1859.

Dr. Johnathon Winbush, executive director of the Beach Institute, was a panelist during the commemoration. Although he had to leave early, he shared an insightful summary of how the Beach Institute is connected to another tragic racial violence event, the Ebenezer Creek Massacre of 1864, and the subsequent legacy of “40 acres and a mule.” He concluded with the following hallmark statement on behalf of the Beach Institute, focusing on the interconnectedness of historical events, their influence on the future, and the bonds formed among those who participate in the commemorations.

I call it pearl stringing information. You hear about these different events that occurred, but what we try to do here is draw a line between them all to make a linkage and connection to show that they all matter- they all make a difference. If we understand the pieces and if we understand the people who are associated with it, that really creates the story. A lot of times in Black history, we say, Did you hear about this? You didn’t hear about that? We think in isolation. But once we do that pearl stringing, taking different bits of information and lining them up, it makes perfect sense of what happened. We have to accept the beauty of our lives, and we have to accept the tragedy, and the problems in terms of the massacres that occurred because they all make a difference. And so this Weeping Time was a remarkable, horrible thing that occurred, but we’re finding synergy in this room right now, today, linking us to dry those tears and create more tears of joy. To find our connections. I’m so happy that we keep commemorating, and we keep going back like that Sankofa bird, moving forward and going back to find our links. ⁴

Panel: “A Genealogy of Place and People.” Weeping Time Commemoration 25′

Every year, there are several events featured as a part of the commemoration: lectures, culinary events, community activities, school events where students learn about the Weeping Time, church services, and community vigils. What they all have in common is unity. Each gathering was organized to connect the past with the present and bring people together. Moods ranged from somber to reflective, and in the spirit of hope, in 2025, the Weeping Time African Unity Festival ended the commemoration on a festive note.

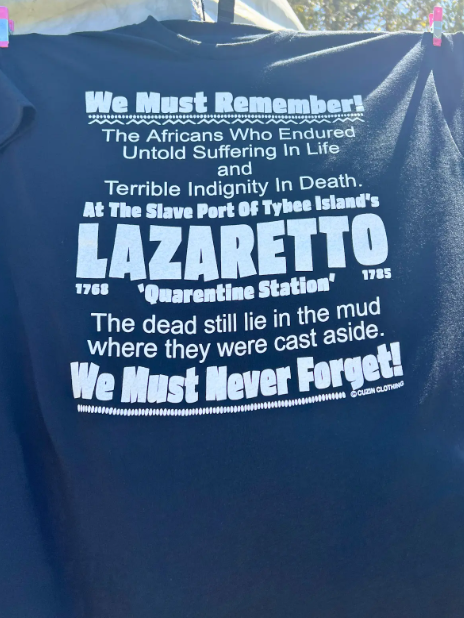

Lazaretto Day

COVID-19 may have been the first time contemporary Westerners became familiar with the premise of quarantining, but this practice dates back to the 14th century as a common method for controlling the spread of disease.⁵ According to the historical marker database, A lazaretto or lazaret is a quarantine station for sea travelers. The term can be used to refer to places- more specifically, isolated islands or mainland buildings- or ships permanently at anchor. 40% of the enslaved people brought to the United States entered through Charleston and Savannah⁶, and all of those who entered via Savannah between January 1768 and October 1785⁷ had to pass through the Tybee Lazaretto. 2025 marked the fifth year that Lazaretto Day was commemorated on Tybee Island, Georgia. It is observed on March 25th, which is the United Nations’ International Day of Remembrance of Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. This commemoration is one of six annual commemorations initiated by the Tybee MLK Human Rights Organization, with the leadership of Julia and Mallory Pearce.

Governor James Wright signed the Lazaretto Act in March 1767.⁸ This act was established in response to the frequent importation of enslaved people through Savannah, necessitating a designated location for quarantining those who may be sick. It specified that a lazaretto be constructed at the westernmost point of Tybee Island, situated within the creek. The language of the Act suggests that the land was to be acquired through what would now be considered eminent domain. Procedurally, when a ship arrived, it was required to anchor for a minimum of fourteen days. During this time, a physician from Savannah would inspect the ship to determine if anyone on board had a deadly communicable disease, such as yellow fever. If at least one person was found to be ill, the boat would moor at the Lazeretto and everyone, including the captain, would be required to remain there until all individuals were cleared. Once the last person was cleared, the vessel had to stay docked for an additional forty days as an extra precaution. If no one fell ill during these forty days, the ship would then be allowed to proceed to Savannah. Just eight months after the Lazaretto began operating, it recorded its first infected arrival of a ship named Gambia, which was carrying captives from Africa. Governor Wright issued a proclamation in the Georgia Gazette, which serves as a source document for the quarantine instructions and procedures for burying the deceased.⁷𐞁⁹

As previously mentioned, the racial violence commemoration events studied by our team were not held to simply mark the date of a tragedy, or cling to the past, but to pay homage to those who were victimized, those who drew and draw strength from them, and the yet unborn. As the Lazeretto Day keynote speaker, Dr. DeGraft-Hanson didn’t just acquaint us with the history of the Tybee Lazeretto, but he poignantly explained the purpose of the occasion.

I want to share a little bit about the importance of recognizing these types of places. It has to do with the people… [Many of the spiritual practices that we] believe in tell us that the human spirit lives forever, so it’s important also that we remember where they are and who they are. And a memorial such as Julia and Tybee MLK have been advocating for is, in my opinion, one of the least things that we need to do. To commemorate is just to be human because when our parents and grandparents pass on, the first thing we do after we bury them is we get a marker for dad, we get a tombstone for grandma. Why? It’s important because you want those who are not here now, your future grandchildren, to be able to go and say that’s great-granddad. They learn not about [their great-grandparents], but about who they are. Because the color of your eyes is partly because by who your great-grandparents were, those you didn’t see. The courage that you have, Julia, is because of some people that you don’t know but who bestowed in you what you are. Your ancestors. We have to acknowledge them, and it is in acknowledging them that we become more human and more humane.

Kwesi DeGraft-Hanson, Lazaretto Day 25′

Yesterday as I was driving here, I heard this on the radio, and I’ll wrap up. It mentioned a memorial that we all know, September 11th. We know that memorials were built in New York City, Pennsylvania, and the D.C. area. Those memorials have long been built. Why were they built? Because it’s important that those people whose lives were tragically taken are remembered, that’s just human. But we’ve not commemorated the Lazaretto 250 something years ago. Here’s what I heard last night driving in. They mentioned that when the plane hit the Pentagon, it affected some trees in the DC area. Those trees have struggled since 9-11, and many of them are dying out. So the concern is we need to replace the trees, which makes sense…This is what caught my attention. Not only are they going to replace the trees, but they mentioned groves of trees as memorials to the trees. Think about that. So, we need to build memorial trees as a commemoration of the trees that were lost or are dying. And I play on those words. A grove of trees, a group of trees. What about a grove of people? What about the graves of people, what about the graves of people at the Lazaretto?⁶ٰ

Works Cited:

- Toure`, A.J (2025, March 1). Personal communication [St. Cyprian Lazeretto Day Keynote Address].

- DeGraft-Hanson, K ( 2025, February 28). Personal communication [Weeping Time A Genealogy of Place and People Panel Discussion].

- Doesticks, Q.K.P (1859 March 9). What Became of the Slaves on a Georgia Plantation? New York Tribune. retrieved from https://archive.org/details/greatauctionsale00does/page/n1/mode/2up

- Winbush, J. ( 2025, February 28). Personal communication [Weeping Time: A Genealogy of Place and People Panel Discussion].

- Conti A. A. (2008). Quarantine Through History. International Encyclopedia of Public Health, 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012373960-5.00380-4

- DeGraft-Hanson, K ( 2025, March 25). Personal communication [Lazaretto Day Keynote Speaker].

- Bridgman Sweeney, K. (2023). “Brief Historical Summary of the Tybee Lazaretto.” Department of Sociology and Anthropology Faculty Publications, Paper 189. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/soc-anth-facpubs/189.

- Marbury, H. and Crawford, W. H., (18020). “1802 Marbury and Crawford’s Digest” (1802). Historical Georgia Digests and Codes.

- https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/ga_code/9 p.344.

- (1768, August 10). A Proclamation. Georgia Gazette retrieved from Georgia Historic Newspapers Archive.